A man stumbles out of a dense rainforest into a village clearing. He sways on his feet, sinking to his knees as another bout of trembling crashes over him. His clothes, once crisp white linen, are torn and discolored with mud, blood and sweat. The villagers cautiously approach. His jaundiced eyes search their faces, pleading for help. It’s 1850. Zambia. And this man — a Scottish explorer — has malaria. The villager healer tries to make him comfortable but her options are few. The closest medical dispensary is 60 miles away and she knows its shelf of malarial treatments is bare. The man’s prospects are bleak.

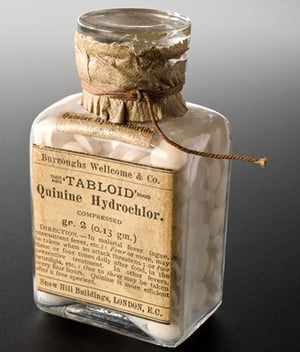

At this precise moment but nearly 6000 miles due East, a Dutch naturalist in Indonesia swats a mosquito on the back of his neck. He clambers down a tree clutching his prize — a rare and beautiful orchid. Catching his breath, a familiar cloud of weaknesses descends on him and he slumps against the tree. He reaches for his pack and produces a small cork-stoppered bottle filled with white powder. He inspects the label: Sulphate of Quinine. Hands shaking, he places a spoonful of the powder in his mouth and washes it down with the last of his whiskey. This man also has malaria. But he has a good chance of keeping it at bay.

What’s the difference between these two scenarios?

Both our heroes were leading daring lives. And through the course of their adventures they were both struck down by the same nasty parasite — plasmodium falciparum — injected into their bloodstream by a passing ne’er-do-well mosquito. But two critical innovations kept our second intrepid naturalist alive: an anti-malarial medicine called quinine, and the elaborate global supply chain that made the life-saving medication available.

Introducing the Cinchona Tree

Before we get to how all of this relates to COVID-19 and its seemingly crippling effect on supply chains across the globe, here’s a quick potted summary of the Cinchona Tree and the global supply chain it generated.

- A Jesuit priest made a not-so-miraculous recovery: No one knows exactly when the Quechua people of the Andean regions of South America discovered that the bark of the Cinchona Tree could cure a deadly fever. Europeans are thought to have stumbled on the tree’s amazing properties in the 17th Century, when a Jesuit priest, treated for fever by locals, made a complete recovery.

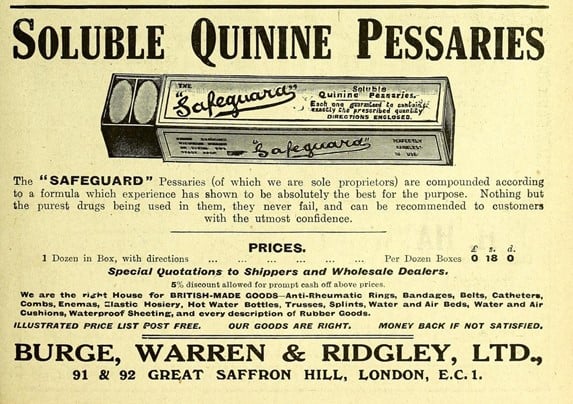

- An empire or two realized they were onto a good thing: In the decades that followed, countless barrels of harvested bark would be transported in cargo ships from Peru to Europe, where it would be refined into quinine — an alkaloid compound derived from the tree’s bark. From there it was distributed across the newly acquired territories of a who’s who of vast and growing European colonial empires.

- Locals wanted to keep their piece of the pie: Realizing the value of the tree, landholders in Peru, Ecuador, Colombia, and Bolivia jealously guarded their monopoly with tight export restrictions on seeds and brutal punishments for smugglers.

- But in the global monopoly game, there can be only one: Fortunes were lost. As the years passed and empires expanded the tree would, inevitably, be smuggled out of its local habitat and produced elsewhere. For a time, Cinchona tree plantations were grown by British landowners in India, but conditions weren’t ideal and production efforts ultimately proved a commercial failure. The Dutch Empire succeeded where the British Empire failed, and established vast Cinchona plantations in Java. Dutch merchants dominated production and armed with a rapidly growing monopoly, carefully controlled quinine prices in their favor for years. Fortunes were made.

- Enter Big Pharma, stage left: And that was the status quo until 1913 when a consortium of pharmaceuticals put a quinine price agreement in place — the first documented example of a corporate pharmaceutical cartel.

What’s this got to do with modern supply chain management, you may ask?

So all that up there is a lot of history. And needless to say, the whole story has a lot more twists and turns. But when it gets down to brass tacks, here’s how this story didn’t go: A bad disease threatened our future, people figured out a cure, and everything went back to normal.

Somewhere between the threat and the bright new future, there was a long and difficult chapter when new systems were built; when the political and economic terrain shifted; when there were winners and losers; and when some shelves had the vital thing someone needed while other shelves remained terrifyingly bare.

Somewhere between the threat and the bright new future, there was a long and difficult chapter when new systems were built; when the political and economic terrain shifted; when there were winners and losers; and when some shelves had the vital thing someone needed while other shelves remained terrifyingly bare.

That in-between chapter might sound oddly familiar.

In 2020, as a strange new disease swept across the globe, consumers were greeted with the alarming sight of empty shelves — in grocery stores and pharmacies, in fact across the length and breadth of retail and manufacturing. People became scared and that terror of going without radiated out across our economy in odd and unpredictable waves. For a few months there, no one could get toilet paper. Disinfectants and masks followed in its wake. When basics like bread and milk began to disappear, empty shelf panic sharpened considerably. The media began to talk about “Covid-19 and The New Normal.”

For a lot of people (businesses too), this was the first time they’d ever given real and serious thought to the vast supply chain that kept their products flowing. The idea that some invisible chain could “go wrong” was as distant and abstract as an explorer with a pith helmet succumbing to an unknown disease in an unexplored corner of a mysterious continent.

Fixing the New Normal

Quinine eventually found its way to every corner of the globe. The supply chain supporting its availability didn’t arrive easily, but by the early 20th Century, quinine was a commonly available treatment in the remotest parts of the world.

Building the quinine supply chain was a vast undertaking, but decades of inventive determination led to a solution. A disease that had taken millions of lives remained deadly, but it became something that needn’t stand in the way of progress.

The COVID-19 pandemic needn’t stand in the way of building a strong supply chain.

None of us can afford to be that fatalistic, using the COVID-19 pandemic as an excuse to explain why shelves meant for your product end up empty. Nor can we sit back and wait this thing out, assuming that sooner or later everything will return to how it was — that’s a recipe for being blindsided again.

Your empty shelf problem is just a human organizational challenge in need of a solution, and IL2000 specializes in finding those solutions. We fix the most formidable supply chain challenges. Just check out our results. We’ve:

- Made extremely heavy products easier to move.

- Helped transform a costly freight operation into a profit center.

- Built customized tools to quickly find the best carrier.

We can solve your supply chain problem too. Want to see a brighter supply chain future? Take the first step today by scheduling a no-obligation supply chain analysis.